Access Granted – But at What Cost?

It’s 6:00 p.m. on Friday – the working week is officially over. A junior finance officer is just about to turn off the lights and leave for the weekend when an urgent call comes in from IT. For some reason, the payroll run wasn’t triggered. The junior finance officer can see exactly what the problem is, but their hands are tied. They simply don’t have the necessary permissions to re-run the payroll.

None of the IT staff will be paid until Monday. HR needs to brace themselves for a lot of very angry calls. What could’ve been a five-minute fix becomes an incident that causes disgruntled employees and a harassed HR team. Lost time. Lost reputation. Lost trust.

Of course, this is just a thought-experiment to illustrate that access controls are supposed to safeguard systems, but when they can’t flex in emergencies – or during periods of reduced staffing – they become roadblocks. The pressure to get things done doesn’t go away. It just finds another route, often through informal, unsanctioned workarounds.

And this challenge becomes even more critical during vacation season. With key team members out of office, backup plans often rely on hastily granted access – or worse, inherited permissions with no clear ownership. Without clear workflows in place, coverage gaps can turn routine incidents into prolonged outages.

On the other end of the spectrum is a different kind of danger: too much access, granted too freely, and left unmonitored.

Take the 2025 Zurich Airport incident. A 20-year-old employee used a colleague’s credentials, without their permission, to access and delete critical baggage handling data. The reason why wasn’t made public, but the results were very public. Thousands of suitcases misrouted. Flights delayed. Travelers stranded. It wasn’t a system glitch or an accident. It was a human exploiting a gap in access control: shared credentials, no oversight, no expiry.

This wasn’t just a failure in judgment. It was a failure in governance. Temporary permissions often feel like a shortcut. But shortcuts around good governance rarely lead to safer or smarter outcomes. They just open new doors to risk.

The risk isn’t only about who has access. It’s about how that access is managed, monitored, and revoked. Agility without control isn’t fast, it’s fragile.

Crisis Culture: How Emergencies Shape Bad Habits

When systems fail, people adapt. And not always in good ways.

Emergencies like a payroll failure on Friday evening expose weak points. But they also create bad habits.

In environments where urgent access isn’t designed into the system, teams resort to improvisation: shared credentials, backdoor workarounds, undocumented escalations. What starts as a one-time emergency fix can quickly become routine – especially if no one goes back to revoke those temporary privileges.

The Zurich Airport case wasn’t an outlier. It was the result of a culture where permissions were treated casually, and oversight was missing. A culture where ‘borrowing a colleague’s login’ was the most expedient way to fix an unexpected problem. Media headlines framed it as a ‘hack’, but the ‘bad actor’ here didn’t hack anything. They walked in through an open door – a door held open by poor habits and the absence of accountability.

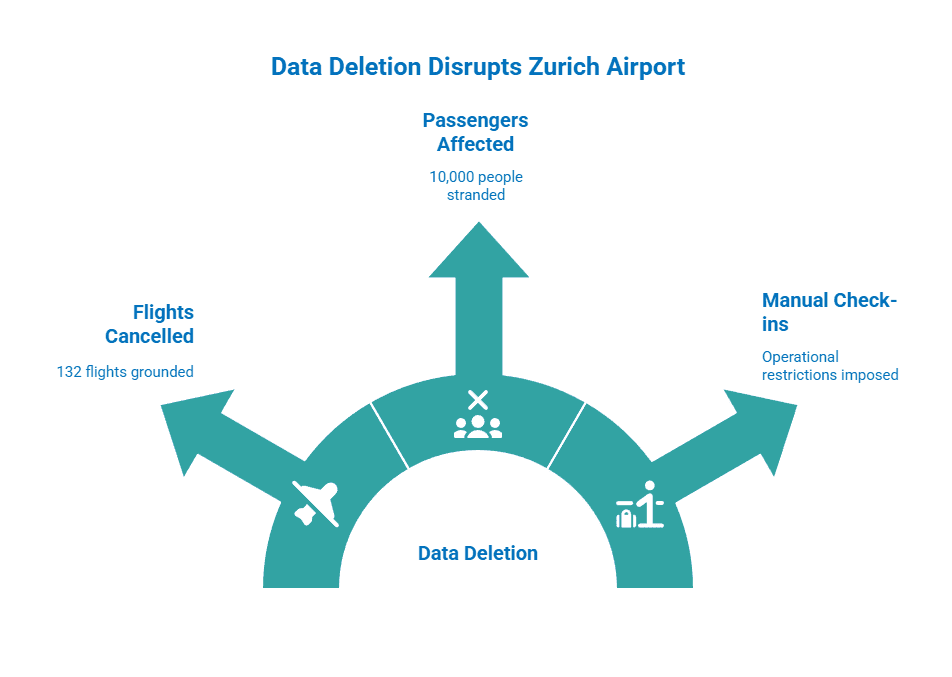

Here’s what the fallout of deleting a stack of data about suitcases looked like in numbers:

- Approximately 132 flights were cancelled at Zurich Airport

- Around 10,000 passengers were affected by these cancellations

- The outage led to significant operational restrictions, including manual passenger check-ins and temporary suspensions of inbound flights due to a shortage of available stands.

Departures from Zurich were not impacted, and by mid-afternoon, full flight operations were restored. But while the exact financial impact of this specific incident hasn’t been publicly disclosed, it’s noteworthy that Swiss International Air Lines reported over CHF 10 million in guest compensation during the first nine months of 2024, attributed to baggage handling disruptions. On top of that, Zurich Airport is now investing approximately CHF 450 million in upgrading its baggage sorting system, aiming to enhance reliability and prevent future disruptions.

Malicious incidents aside, humans are wired to take the path of least cognitive resistance, leaving as much brain capacity as possible in reserve to escape from a charging woolly mammoth. So, once someone learns that bypassing process is easier than following it, it becomes the path of least resistance. And when staff go on holiday or during skeleton shifts, that temptation only grows.

This is what happens when urgency outpaces governance.

And the worst part? These access failures often stay invisible until it’s too late. Logs may record the “who” and “when,” but they rarely illuminate the “why.” And when access isn’t governed by purpose and context, risk becomes ambient – ever-present, but easy to ignore.

Designing for urgency isn’t a nice-to-have. These days it’s essential infrastructure.

You don’t have to choose between agility and safety. But you do have to choose to prepare. Because once you’re in a crisis, it’s too late to start writing the emergency playbook.

And it’s not about just one tool, or a new rule. It’s a cultural decision: Do we treat access as a convenience, or as a responsibility?

Temporary by Design: What Good Looks Like

So, what does a resilient, responsive access model look like?

It starts with designing for exception handling, not just regular operations. That means building access workflows that can adapt to real-world urgency – without bypassing the governance layer.

One example of a tool built for this exact need is Firefighter, a controlled access module in the Mesaforte suite from wikima4.

Firefighter allows organisations to grant elevated privileges temporarily, purposefully, and audibly. Developed with emergency use in mind – hence the name, Firefighter – it includes built-in logging, expiry mechanisms, and real-time oversight.

Get Your Free Firefighter Guide

Tools like this aren’t about denying access, they’re about making access trustworthy by default. Firefighter treats privilege not as an open door but as a managed asset. And perhaps most importantly, it reframes the conversation from “How do we limit access?” to “How do we give access well?”

I’m sure we can all agree that life is never perfect. And good systems shouldn’t assume things will always go right. They also need to plan for what happens when they don’t.

Building the Habit of Safe Access

Great tools only take you halfway. The rest depends on culture.

Organisations need to normalise time-limited access as part of the operational DNA – not just for emergencies, but for deployments, testing, maintenance, and escalations.

When teams trust the system to grant them what they need safely, quickly, and transparently, they stop needing to circumvent it. That’s the difference between control and trust: the best governance feels invisible until it’s needed.

Returning to the Zurich example: this wasn’t a story of one engineer making one mistake. It was a system-wide lesson about how fragile even the most robust infrastructure can be if access isn’t actively managed.

Modern businesses in all industries need to stop treating temporary permissions as edge cases. They are the norm and can lead to big problems if managed badly. Like the May 2025 cybersecurity incident at Victoria’s Secret, which had to enact emergency protocols to contain unauthorised access, resulting in the postponement of its first-quarter earnings release. Or the case in May 2023 where two former Tesla employees leaked over 23,000 internal files, which included personal identifiable information (PII) of employees, customers’ financial details, proprietary production data, and records of user complaints about Tesla’s electric vehicles.

And the more distributed and dynamic our systems become, the more important it is to ensure access control adapts just as fast.

Good governance isn’t static. It adapts – just like the threats do.

It’s time to stop thinking of temporary access as a workaround. Let’s treat it like a design pattern. With the right tools, the right mindset, and the right habits, we can make urgent access safe, structured, and sustainable.

Because in the end, access is power. And power – if borrowed – should always come with plan to give it back.